Chapter 5 HW

1.

a.

Defined Space:

- A coordinate system (e.g., Cartesian, polar) is necessary to describe the position, velocity, and acceleration of an object.

- Why it’s needed: Without a reference frame, it is impossible to quantify motion or compare it across different scenarios. The coordinate system provides a basis for measuring displacement, velocity, and acceleration.

Defined Time:

- The window over which we are analyzing the object.

- Why it’s needed: Kinematic equations rely on initial conditions to predict future motion. Without a “start”, it’s impossible to solve for unknowns like final velocity, displacement, or time.

b.

Linear Motion vs. Angular Motion

- Linear Motion: Motion along a straight line, where all parts of the object move the same distance at the same time.

- Example: A car moving in a straight line on a highway.

- Angular Motion: Motion along a circular path, where objects rotate about a fixed axis.

- Example: A spinning Ferris wheel.

Rectilinear Motion vs. Curvilinear Motion

- Rectilinear Motion: Motion along a straight path.

- Example: A train moving on a straight track.

- Curvilinear Motion: Motion along a curved path.

- Example: A car driving around a circular race track.

Distance Covered vs. Displacement

- Distance Covered: The total path length traveled by an object, regardless of direction. It is a scalar quantity.

- Example: Running 5 km around a circular track.

- Displacement: The shortest distance between the initial and final positions, with direction. It is a vector quantity.

- Example: Running 5 km around a circular track and ending at the starting point results in zero displacement.

Velocity vs. Acceleration

- Velocity: The rate of change of displacement with respect to time. It is a vector quantity (includes direction).

- Example: A car moving at 60 km/h north.

- Acceleration: The rate of change of velocity with respect to time. It is also a vector quantity.

- Example: A car increasing its speed from 0 to 60 km/h in 10 seconds.

Average Velocity vs. Instantaneous Velocity

- Average Velocity: The total displacement divided by the total time taken. It gives an overall measure of motion.

- Example: A car travels 100 km north in 2 hours; its average velocity is 50 km/h north.

- Instantaneous Velocity: The velocity of an object at a specific moment in time.

- Example: A car’s speedometer reading at a particular instant, such as 60 km/h at 3:00 PM.

2.

a.

| Velocity Scenario | Position Change | Acceleration | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive and increasing | Moving forward and speeding up. | Positive acceleration | Acceleration is in the same direction as velocity, causing the object to speed up. |

| Positive but staying constant | Moving forward at a steady speed. | Zero acceleration | No change in velocity means no acceleration. |

| Positive but decreasing | Moving forward but slowing down. | Negative acceleration (deceleration) | Acceleration is opposite to velocity, causing the object to slow down. |

| Negative and increasing in magnitude | Moving backward and speeding up. | Negative acceleration | Acceleration is in the same direction as velocity (both negative), causing the object to speed up. |

| Negative and not changing | Moving backward at a steady speed. | Zero acceleration | No change in velocity means no acceleration. |

| Negative and decreasing in magnitude | Moving backward but slowing down. | Positive acceleration | Acceleration is opposite to velocity, causing the object to slow down. |

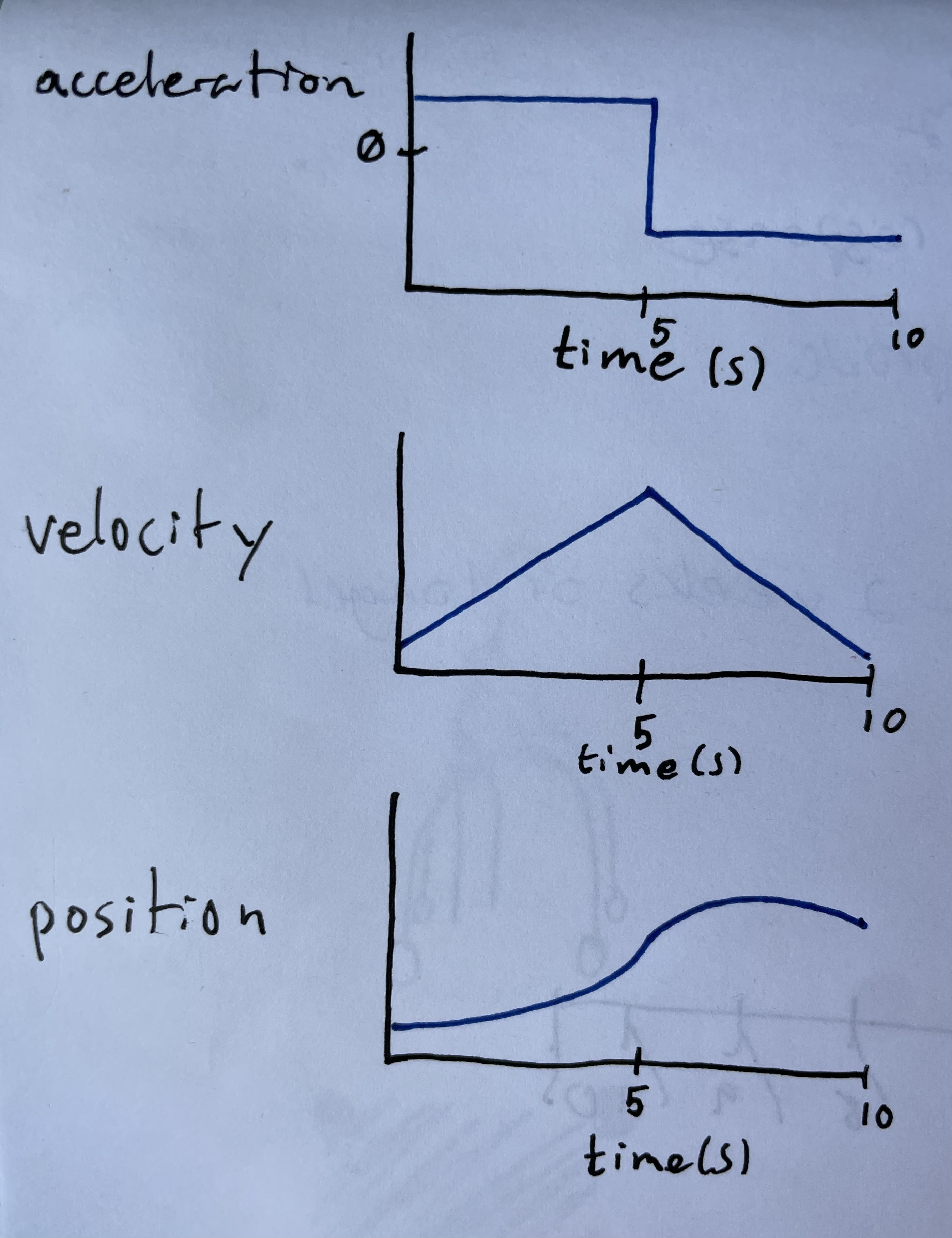

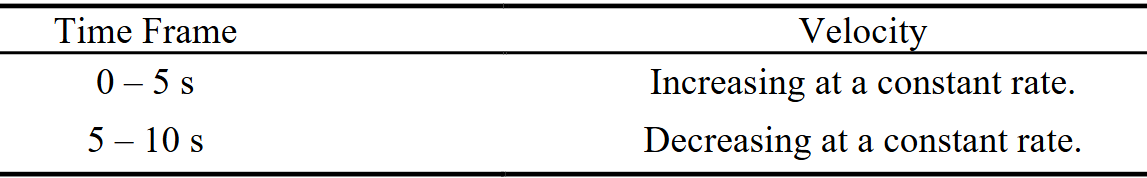

b.

3.

a.

Projectile motion is the motion of an object influenced only by gravity (and air resistance if considered). In other words, an object in free fall. The path followed by the object is called a trajectory, which is typically parabolic in shape. Projectile motion can be analyzed by breaking it into horizontal and vertical components, where:

- Horizontal speed is uniform (constant velocity, no acceleration assuming negligible air resistance).

- Vertical speed is accelerated due to gravity (acceleration = $ g = 9.8 , \text{m/s}^2 $ downward).

b.

Long Jump or High Jump in Track and Field: The athlete’s center of mass follows a parabolic trajectory during the jump.

Diving: A diver’s center of mass follows a projectile motion as they leap off the diving board.

Gymnastics (Vault or Floor Exercise): A gymnast’s center of mass follows a projectile trajectory during flips or leaps.

c.

Projectile Motion: The motion of an object launched into the air or in free fall, influenced by gravity.

Projection Angle: The angle at which the object is launched relative to the horizontal.

Projection Height: The vertical distance between the launch point and the landing surface.

Projection Velocity: The initial speed and direction at which the object is launched.

d.

Projection Angle:

- Determines the shape and range of the trajectory.

- Optimal Angle: For maximum horizontal range (ignoring air resistance), the optimal angle for a given speed is 45 degrees.

- Low Angle (e.g., 30 degrees): Shorter range, flatter trajectory.

- High Angle (e.g., 60 degrees): Higher peak, shorter range.

- Example: A cannonball fired at 45 degrees travels farther than one fired at 30 or 60 degrees.

Projection Height:

- Affects the time of flight and the horizontal distance traveled.

- Higher Projection Height: Increases the time of flight and the horizontal range.

- Example: A ball thrown from a tall building travels farther than one thrown from ground level.

Projection Velocity:

- Determines the speed and energy of the projectile, affecting both height and range.

- Higher Velocity: Increases the maximum height, range, and time of flight.

- Example: A baseball thrown at 30 m/s travels farther and higher than one thrown at 10 m/s.

4.

1. $ v_f = v_i + a \cdot t $

Description:

This formula calculates the final velocity ($ v_f $) of an object by adding its initial velocity ($ v_i $) to the product of its acceleration ($ a $) and the time elapsed ($ t $). It is derived from the definition of acceleration, which is the rate of change of velocity over time.

When to Use:

- You would use this formula when you know the initial velocity, acceleration, and time, and you want to find the final velocity of an object.

- Example: A car accelerates from rest ($ v_i = 0 $) at $ 2 , \text{m/s}^2 $ for 5 seconds. What is its final velocity?

2. $ v_f^2 = v_i^2 + 2 \cdot a \cdot d $

Description:

This formula relates the final velocity ($ v_f $) of an object to its initial velocity ($ v_i $), acceleration ($ a $), and the distance traveled ($ d $). It is derived from the kinematic equations and eliminates the need to know the time elapsed.

When to Use:

- You would use this formula when you know the initial velocity, acceleration, and distance, and you want to find the final velocity of an object.

- Example: A ball is thrown upward with an initial velocity of $ 20 , \text{m/s} $. How fast is it moving after traveling $ 15 , \text{m} $ upward?

3. $ d = v_i \cdot t + \frac{1}{2} a \cdot t^2 $

Description:

This formula calculates the distance traveled ($ d $) by an object based on its initial velocity ($ v_i $), the time elapsed ($ t $), and its acceleration ($ a $). It accounts for both the constant velocity component ($ v_i \cdot t $) and the acceleration component ($ \frac{1}{2} a \cdot t^2 $).

When to Use:

- You would use this formula when you know the initial velocity, acceleration, and time, and you want to find the distance traveled by an object.

- Example: A car starts from rest ($ v_i = 0 $) and accelerates at $ 3 , \text{m/s}^2 $ for 4 seconds. How far does it travel?

Summary:

- $ v_f = v_i + a \cdot t $: Use when solving for final velocity given initial velocity, acceleration, and time.

- $ v_f^2 = v_i^2 + 2 \cdot a \cdot d $: Use when solving for final velocity given initial velocity, acceleration, and distance.

- $ d = v_i \cdot t + \frac{1}{2} a \cdot t^2 $: Use when solving for distance traveled given initial velocity, acceleration, and time.